Hello World,

This year's installment of the GNU Hacker's Meeting is just a month away.

- When: Thursday July 19th until Sunday July 22th

- Where: Düsseldorf

As in previous years, the fun starts on Thursday with an informal hacking / social evening followed by talks (as well as more hacking) Friday through Sunday.

If you are planning on coming, we request that you register soon by emailing ghm-registration@gnu.org as we have a limit amount of space.

Note: We are also still accepting presentation proposals.

See you soon!

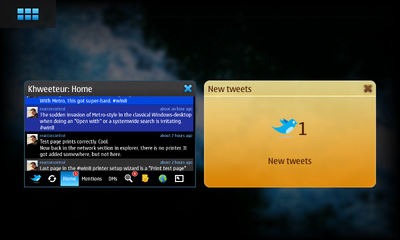

I was recently hunting down a slightly annoying usability bug in Khweeteur, a Twitter / identi.ca client: Khweeteur can notify the user when there are new status updates, however, it wasn't overlaying the notification window on the application window, like the email client does. I spent some time investigating the problem: the fix is easy, but non-obvious, so I'm recording it here.

A notification window overlays the window whose WM_CLASS

property matches the specified desktop entry (and is correctly

configured in

/etc/hildon-desktop/notification-groups.conf). Khweeteur was doing

the following:

import dbus

bus = dbus.SystemBus()

notify = bus.get_object('org.freedesktop.Notifications',

'/org/freedesktop/Notifications')

iface = dbus.Interface(notify, 'org.freedesktop.Notifications')

id = 0

msg = 'New tweets'

count = 1

amount = 1

id = iface.Notify(

'khweeteur',

id,

'khweeteur',

msg,

msg,

['default', 'call'],

{

'category': 'khweeteur-new-tweets',

'desktop-entry': 'khweeteur',

'dbus-callback-default'

: 'net.khertan.khweeteur /net/khertan/khweeteur net.khertan.khweeteur show_now',

'count': count,

'amount': count,

},

-1,

)

This means that the notification will overlay the window whose

WM_CLASS property is khweeteur. The next step was to figure out

whether Khweeteur's WM_CLASS property was indeed set to khweeteur:

$ xwininfo -root -all | grep Khweeteur

0x3e0000d "Khweeteur: Home": ("__init__.py" "__init__.py") 800x424+0+56 +0+56

^ Window id ^ WM_CLASS (class, instance)

$ xprop -id 0x3e0000d | grep WM_CLASS

WM_CLASS(STRING) = "__init__.py", "__init__.py"

Ouch! It appears that a program's WM_CLASS is set to the name of its "binary". In this case, /usr/bin/khweeteur was just a dispatcher that executes the right command depending on the arguments. When starting the frontend, it was running a Python interpreter. Adjusting the dispatcher to not exec fixed the problem:

$ xwininfo -root -all | grep Khweeteur

0x3e00014 "khweeteur": ("khweeteur" "Khweeteur") 400x192+0+0 +0+0

0x3e0000d "Khweeteur: Home": ("khweeteur" "Khweeteur") 800x424+0+56 +0+56

While working on the Woodchuck support in gPodder, I decided to profile the code. Reading the Python manual, I thought it would be as easy as:

import cProfile

cProfile.run('foo()')

On both Debian and Maemo, this results in an import error:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "/usr/lib/python2.6/cProfile.py", line 36, in run

result = prof.print_stats(sort)

File "/usr/lib/python2.6/cProfile.py", line 80, in print_stats

import pstats

ImportError: No module named pstats

To my eyes, this looks like I need to install some package. This is

indeed the case: the python-profiler package

provides the pstats module. Unfortunately, python-profiler is not

free. There's a depressing back story involving ancient

code and missing rights holders.

If you're on Debian, you can just install the python-profiler

package. Alas, the package does not appear to be compiled for Maemo.

Happily, kernprof works around this and is easy to use:

# wget http://packages.python.org/line_profiler/kernprof.py

# python -m kernprof /usr/bin/gpodder

Kernprof saves the statistics in the file program.prof in the

current directory (in this case, it saves the data in gpodder.prof).

To analyize the data, you'll need to copy the file to a system that

has python-profiler installed. Then run:

# python -m pstats gpodder.prof

Welcome to the profile statistics browser.

% sort time

% stats 10

Tue Nov 1 13:09:54 2011 gpodder.prof

105542 function calls (101494 primitive calls) in 117.449 CPU seconds

Ordered by: internal time

List reduced from 1138 to 10 due to restriction <10>

ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function)

1 57.458 57.458 69.012 69.012 {exec_}

1 16.052 16.052 26.417 26.417 /usr/lib/python2.5/site-packages/gpodder/qmlui/__init__.py:405(__init__)

1 8.591 8.591 13.790 13.790 /usr/lib/python2.5/site-packages/gpodder/qmlui/__init__.py:24(<module>)

60 7.041 0.117 7.041 0.117 {method 'send_message_with_reply_and_block' of '_dbus_bindings.Connection' objects}

3 6.357 2.119 7.469 2.490 {method 'reset' of 'PySide.QtCore.QAbstractItemModel' objects}

36 2.636 0.073 2.636 0.073 {method 'execute' of 'sqlite3.Cursor' objects}

1 2.283 2.283 2.284 2.284 {method 'setSource' of 'PySide.QtDeclarative.QDeclarativeView' objects}

1 1.848 1.848 1.848 1.848 /usr/lib/python2.5/site-packages/PySide/private.py:1(<module>)

2 1.789 0.895 1.789 0.895 {posix.listdir}

1 0.765 0.765 4.234 4.234 /usr/lib/python2.5/site-packages/gpodder/__init__.py:20(<module>)

The statistics browser is relatively easy to use (at least for the

simple things I've wanted to see so far). Help is available online

using its help command.

Khweeteur is a great twitter and identi.ca client for Maemo. One feature I particularly like is its support for queuing of status updates, which is useful when connectivity is poor or non-existent (which, for me, is typically when something tweet-worthy happens). It also supports multiple accounts, e.g., a twitter account and an identi.ca account.

Khwetteur can automatically download updates and notify you when something happens. Enabling this option causes Khwetteur to periodically perform updates whenever there is an internet connection---whether it is a WiFi connection or via cellular. This is unfortunate for those, who like me, have limited data transfer budgets.

Deciding when to transfer updates is exactly what Woodchuck was designed for, and recently, I added Woodchuck support to Khweeteur. Now, if Woodchuck is found, Khweeteur will rely on it to determine when to schedule updates (of course, you can still manually force an update whenever you like!).

While modifying the code, I also made a few bug fixes and some small enhancements. Two improvements that, I think, are noteworthy are: displaying unread messages in a different color from read messages, and indicating when the last update attempt occured.

You can install the Woodchuck-enabled version of Khweeteur on your N900 using this installer. You'll also need to install the Woodchuck server, to profit from the Woodchuck support. Hopefully, the version in Maemo extras will be updated soon!

Other Woodchuck-enabled software for the N900 include:

- FeedingIt: An RSS reader

- APT Woodchuck: A software update scheduler for Maemo5

If you are interested in adding Woodchuck support to your software, let me know either via email or join #woodchuck on irc.freenode.net.

I'll be at the N9 Hackathon this weekend in Vienna. Sunday morning (October 9th) at 10am, I'll give a presentation about Woodchuck. I'll talk a bit about Woodchuck's motivation and a fair amount about Woodchuck's architecture as well as what we hope to learn from the user study and how we planning on using it to evaluate different scheduling algorithms. If you are around, you should come by!

I've finished an initial port of Woodchuck to Harmattan. To get it,

you need to manually add the source repository: Harmattan's

application manager does not support .install files. Add the

following to /etc/apt/sources.list.d/hssl.list:

deb http://hssl.cs.jhu.edu/~neal/woodchuck harmattan harmattan

Then, run apt-get update.

The following packages are available: the Woodchuck server (package: murmeltier), the Python bindings (package: pywoodchuck) and the Glib-based C bindings (libgwoodchuck and libgwoodchuck-dev).

smart-storage-logger, the software for the user behavior study, has not yet been ported: I'm still trying to figure aegis out.

If you are interested in adding Woodchuck support to your software,

see the HOWTO and the documentation. You

can also email me or visit #woodchuck on irc.freenode.net (my nick is

neal).

At the recent GNU Hackers Meeting, I gave a talk about Woodchuck. (I'll publish another post when the video is made available.) The talk resulted in a lot of great feedback including a question from Arne Babenhauserheide whether Woodchuck could be used to automatically synchronize git or mercurial repositories.

I hadn't considered using Woodchuck to synchronize version control respoitories, but it is a fitting application of Woodchuck: some data is periodically transferred over the network in the background. I immediately saw two major applications in my own life: a means to periodically push changes to a personal back up repository; and automatically fetching change sets so that when I don't have network connectivity, I still have a recent version of a repository that I'm tracking.

I decided to implement Arne's suggestion. It's called VCS Sync. To configure it, you create a file in your home directory called .vcssync. The file is JSON-based with the extension that lines starting with // are accepted as comments. The file has the following shape:

{

"directory1": [ { action1 }, { action2 }, ..., { actionM } ],

"directory2": [ { action1 }, { action2 } ],

...

"directoryN": [ { action1 } ],

}

That is, there is a top-level hash mapping directories to arrays of actions. An action consists of four possible arguments: 'sync' (either 'push' or 'pull'), 'remote' (the remote repository, default: origin), 'refs' (the set of branches, e.g., +master:master, default: 'master') and 'freshness' (how often to perform the action, in hours).

Here's an example configuration file:

// To register changes, run 'vcssync -r'.

{

"~/src/woodchuck": [

// Pull daily.

{"sync": "pull", "remote": "origin", "freshness": 24},

// Backup every tracked branch every few hours.

{"sync": "push", "remote": "backups", "refs": "+*:*", "freshness": 3}

],

"~/src/gpodder": [

// Pull every few days.

{"sync": "pull", "remote": "origin", "freshness": 96}

]

}

VCS Sync automatically figures out the repository format and invokes the right tool (currently only git and mercurial are supported; patches for other VCSes are welcome).

After you install the configuration file, you need to run 'vcssync -r' to inform Woodchuck of any changes to the configuration file.

You can use this on the N900, however, because this is a programmer's tool and you need to edit a file to use it, it is not installable using the hildon application manager. Instead, you'll need to run 'apt-get install vcssync' from the command line (the package is in the same repository as the Woodchuck server). If you encounter problems, consult $HOME/.vcssync.log.

I also use this script on my laptop, which runs Debian. Building packages for Debian is easy, just check out woodchuck and use dpkg-buildpackage:

git clone http://hssl.cs.jhu.edu/~neal/woodchuck.git

cd woodchuck

dpkg-buildpackage -us -uc -rfakeroot

This (currently) generates eight packages. In addition to vcssync, you'll also need to install murmeltier (my Woodchuck implmentation), and pywoodchuck (a Python interface to Woodchuck).

One of the arguments for [Woodchuck][http://hssl.cs.jhu.edu/~neal/woodchuck] is that it can save energy. In this post, I want to examine that claim a bit more quantitatively.

To determine whether or not Woodchuck can save energy, we first need to know approximately how much energy the activities we are interested in consume. To measure this, I charged my N900 until the battery was full, then I started some activity and let it run until the device turned off. Every five minutes, I queried the battery's state (voltage, mAh and whether the device was being charged) and wrote it to an SQLite database. The activities that I measured were: streaming or playing an mp3 file at various encodings, downloading over WiFi at different speeds, having the LCD on, and idling. Some of the results are summarized in the table below. Keep in mind that a full charge has approximately 18 kWs (= 5 Wh).

| Data Acquisition | Activity | Watts | Energy Consumed Relative to Idle |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3G | Play 56 Kb/s stream | 1.00 | 12.5 |

| Edge | Play 56 Kb/s stream | 0.96 | 12.0 |

| WiFi | Play 56 Kb/s stream | 0.75 | 9.3 |

| Flash | Play 56 Kb/s files | 0.28 | 3.5 |

| Flash | Play 128 Kb/s files | 0.27 | 3.4 |

| Flash | Play 320 Kb/s files | 0.32 | 4.0 |

| WiFi | Download at 4.7 Mb/s | 1.23 | 15.4 |

| WiFi | Download at 1.0 Mb/s | 0.91 | 11.4 |

| WiFi | Download at 256 Kb/s | 0.76 | 9.5 |

| None | Idle, LCD on | 0.27 | 3.4 |

| None | Idle | 0.08 | 1 |

The first thing to notice is that streaming over a network connection is expensive: streaming over 3G consumes 20% of the N900's battery capacity per hour. Although it is possible to save a bit of energy by using Edge or WiFi, the improvement is marginal. Playing back audio data saved on flash requires significantly less energy---just 30% as much. In other words, if all you do is use your N900 to listen to audio, listening to audio data saved on flash will allow you to listen to more than 3 times as much audio on a single battery charge than if you were to stream that data.

It is not always possible to ensure that the data is saved on flash. In this case, the best approach is to download the data as fast as possible: although downloading over WiFi at 4.7 Mb/s (the maximum sustainable throughput I observed) requires more energy than downloading at, say, 256 KB/s, the required energy per bit is significantly lower.

To put these values in perspective, I measured how much energy the system consumes at idle and with the LCD on. I think it is not surprising that having the LCD on consumes significantly more power than not, however, I was surprised that the network uses 3 times as much energy as having the LCD on.

What do these values mean for Woodchuck? Woodchuck tries to schedule downloads to occur when conditions are good. In terms of energy, conditions are best when the device is connected to the mains. I charge my N900 about every two days. Only updating my subscriptions every two days is not often enough: I don't want the news from a day and a half ago; many blogs that I read are updated daily; and, my calendaring information should be synchronized constantly. In this case, fetching the data as fast as possible over WiFi when the signal is strong is the next best approach.

To understand the possible savings, consider the case where 8 hours of audio, about 200~MB of data, are prefetched over WiFi. At 4.7~MB/s, this requires 420~Ws (2.5% of the battery's capacity). If a user listens to 30 minutes of audio (25~MB) on the commute home, only an additional 480~Ws (2.7% of the battery's capacity) are required. Streaming 30 minutes of audio over 3G requires 1800~Ws, twice the amount of energy to prefetch 8 times the data and listen to the same audio. Thus, even with a cache hit rate of 12%, prefetching uses just half of the energy needed to stream.

As part of some Woodchuck-related work, I've done a fair amount of Python programming on Maemo. Python, being an interpreted language, runs the source code; there is no need to compile it to some binary representation as is the case with C. This is a great convenience when developing for a device such as the N900: there is no need to compile the code and copy the resulting binaries; I just edit the code on the device and run it. The trade-off is that I need to edit the files directly on the device: but, I want my Emacs (qemacs is not enough!), git and the regular GNU tools. It turns out that I was able to get pretty close.

Using Emacs to edit files on the N900 does not necessarily mean running Emacs on the N900: Emacs' tramp mode makes it possible to edit files on another system! I had read about tramp mode in the past, but most systems I use already have Emacs installed, so I never bothered to investigate it further (or at least, it was easier to install Emacs than learn about tramp mode). Using tramp mode to edit a file is embarrassingly easy: you just prefix the login information to the filename that you want to edit. In my case, I add '/user@n900:' to access my home directory on my N900. (To avoid constantly typing in your password, you'll want to add an ssh key to your $HOME/.ssh/authorized_keys file on your device).

Tramp mode is not just for editing: many Emacs functions support tramp. For instance, tab completion knows about tramp, as does dired. Even grep-find is tramp enabled: tramp knows how to run grep and find on the remote machine!

grep-find assumes relatively feature-complete tools. By default, the N900 includes busybox's grep and find, which have rather limited functionality. Happily, Thomas Tanner has packaged many of the GNU tools for Maemo and they are just an apt-get install away. (The packages you need are: grep-gnu, sed-gnu, findutils-gnu, coreutils-gnu, and diffutils-gnu.)

Installing Thomas's packages does not immediately make grep-find work: the packages do not replace the busybox tools; the binaries are installed in /usr/bin/gnu, which is not in the user's default path. To fix this problem, I first installed bash and edited my .bashrc file to read:

PATH=/usr/bin/gnu:$PATH export PATH

And my .bash_profile to read:

. $HOME/.bashrc

I also changed the user's default shell to bash using chsh. Now when I run grep at the command line, I get GNU grep, not Busybox's.

This is still not enough to get grep-find to work: by default, tramp does not respect the PATH variable on the remote machine. (See for more details.) This behavior can be overridden by adding the following to your .emacs file:

(require 'tramp) (add-to-list 'tramp-remote-path 'tramp-own-remote-path)

Now, Emacs's grep-find function works.

The last piece of the puzzle is working with git repositories. My primary interface to git is via Magit. Unfortunately, Magit v0.7, which is distributed with Debian Squeeze, does not fully support tramp mode. Magit v1.0, however, does and it is available in Debian testing. (Note: if you are a Magit v0.7 user and you customized magit-diff-options, you'll need to change the value from a string to a list, e.g., '(setq magit-diff-options '("--patience"))')

This set up is great and I'm happy. As a final tweak, I tend to use USB networking, because access over WiFi has a fair amount of latency.

The following text is from the introduction of the HOWTO I've written explaining how to modify a program to use Woodchuck. The focus is on the Python interface, but it should be helpful to anyone who wants to modify an application to use Woodchuck. This document, unlike the detailed documentation, should be a bit easier to digest if you are just getting started with Woodchuck. If questions still remain, feel free to email me or ask for help on #woodchuck on irc.freenode.net.

Introduction

Woodchuck is a framework for scheduling the transmission of delay tolerant data, such as RSS feeds, email and software updates. Woodchuck aims to maximize data availability (the probability that the data the user wants is accessible) while minimizing the incurred costs (in particular, data transfer charges and battery energy consumed). By scheduling data transfers when conditions are good, Woodchuck ensures that data subscriptions are up to date while saving battery power, reducing the impact of data caps and hiding spotty network coverage.

At the core of Woodchuck is a daemon. This centralized service reduces redundant work and facilitates coordination of shared resources. Redundant work is reduced because only a single entity needs to monitor network connectivity and system activity. Further, because the daemon starts applications when they should perform a transfer, applications do not need to wait in the background to perform automatic updates thereby freeing system resources. With respect to the coordination of shared resources: the cellular data transmission budget and the space allocated for prefetched data need to be allocated among the various programs.

Applications need to be modified to benefit from Woodchuck. Woodchuck needs to know about the streams that the user has subscribed to and the objects which they contain as well as related information such as an object's publication time. Woodchuck also needs to be able to trigger data transfers. Finally, Woodchuck's scheduler benefits from knowing when the user accesses objects. In my experience, the changes required are relatively non-invasive and not difficult. This largely depends, however, on the structure of the application.

...

I designed Woodchuck's API to be easy to use. A major goal was to allow applications to progressively add support for Woodchuck: it should be possible to add minimal Woodchuck support and gain some benefit of the services that Woodchuck offers; more complete support results in higher-quality service.

To support Woodchuck, an application needs to do three things:

- register streams and objects;

- process upcalls: update a stream, transfer an object, and, optionally, delete an object's files; and,

- send feedback: report stream updates, object downloads and object use.

The rest of this document is written as a tutorial that assumes that you are using PyWoodchuck, the Python interface to Woodchuck. If you are using libgwoodchuck, a C interface, or the low-level DBus interface, this document is still a good starting point for understanding what your application needs to do.